Le 18 avril 2014, les gouvernements de 86 pays réunis à Tokyo pour le Forum Global TVA de l’OCDE ont adopté le projet de « Principes directeurs internationaux pour la TVA ».

Ces principes visent à établir des normes dans deux domaines clés :

- assurer la neutralité de la TVA, c’est-à-dire que la TVA ne s’applique que sur la consommation finale, ne pèse pas sur les entreprises et repose sur un traitement équivalent des entreprises domestiques et des entreprises et transactions internationales ;

- garantir l’application de la TVA aux prestations de services internationales B2B dans le pays de destination.

Le Forum Global TVA a été l’occasion dans un premier temps de faire le point sur les développements récents en matière de TVA. Michel Aujean était chargé de situer le cadre du débat. Le fil rouge de son intervention est reproduit ci-après :

Global VAT policy trends and developments: A few introductory remarks on the evolution of VAT systems

- Although the principles of a VAT system are relatively simple, mostly based across the world on the invoice-credit approach, VAT is becoming more and more complex in its day-to-day practical application, notably as transactions become more and more international in their nature. This complexity is affecting its global efficiency, not only at the administration level but more and more at the firm level. Due to this VAT has become a subject of tax planning in many situations and has seen its compliance costs appear as one of the most expensive obligations.

- According to many surveys on the qualities and attractiveness of tax systems, firms attach the greatest importance to legal certainty and simplicity. We all know that the simplest and most efficient and less distortive systems are those with broad bases and moderate rates. This logic remains the best plea for broadening the tax bases. What we have seen recently, exacerbated by the economic and financial crisis, is most of the time characterized by substantial increase in rates and only moderate broadening of the bases. The IMF reports that during the period 2010-13, out of 43 advanced and emerging economies, 19 have increased their VAT rates and 14 have broadened their VAT bases. During the same period, 14 of the 33 OECD member countries having a VAT have increased their standard VAT rates.

- One of the politically most difficult question concerns the role of reduced VAT rates. From the 2012 VAT Forum as well as from the discussion that took place at the Brussels Tax Forum last November, it appears that most experts are of the view that reduced VAT rates are neither socially efficient nor economically wise (notably as they contribute to make the system more complex). Increasing the efficiency of VAT systems would call for the elimination of most/all reduced rates. In policy terms this is much more difficult and the recent example of reduced rates being illegally extended to on-line products by some Member States of the EU show how difficult it might be to eliminate reduced rates once they are in place ! Recent OECD research on the effectiveness of reduced rates and exemptions (to be presented under Session 6 of the Global Forum) shows that VAT reduced rates are a highly inefficient means of providing support to the poorer households and that targeted transfers are a far more efficient means of redistributing to the poor (although they cannot fully compensate all losers from a single-rate reform).

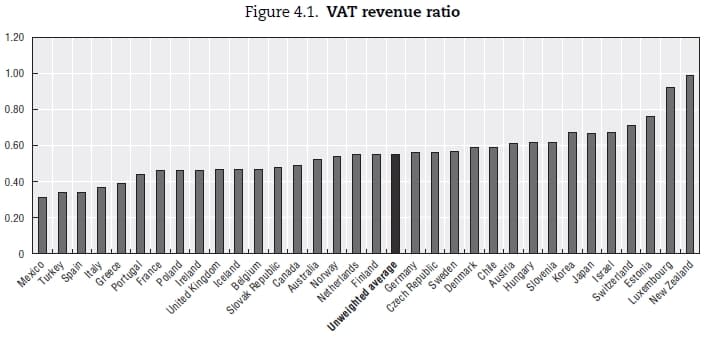

- Coming to the VAT Revenue ratio, or “C-efficiency” (the ratio between the VAT revenue effectively collected and the potential VAT revenue that could be collected if all final consumption was taxed at the standard rate). The IMF reports that in advanced economies C-efficiency has been flat over the last 20 years at only about 60% (but France is below 45% !), while it has been increasing in emerging markets and low-income countries but is still below 50% (see below, Figure 4.1 from IMF report).

The OECD reports about the same figures on average for its member countries. How to improve it ? The reply clearly differs between the two groups of countries. Two main factors can explain the C-inefficiency : a “policy gap” (where VAT is not applied at a single rate and/or not to all consumption, notably due to exemptions) and a “compliance gap” (where implementation of VAT is imperfect). In advanced economies, the policy gap is the main determinant of the lack of efficiency, reflecting extensive exemptions and out-of-scope provisions as well as frequent use of multiple rates. The IMF estimates that halving the policy gap would on average raise 2,3 % of GDP (of which a substantial part would remain even after adjusting social transfers to protect the poorest from price increases subsequent to the elimination of multiple rates) while halving the compliance gap would only bring 0.4% of GDP ! In emerging markets, compliance gaps are much larger and problematic, notably in countries having implemented sub-national VAT systems leading to cascading and high complexity.

- There is substantial scope for broadening the scope of VAT, notably in advanced economies like the EU countries where the VAT rules defining the scope (and the resulting out-of-scope activities and transactions) and the exemptions date from the 70’s ! Initiatives have been taken looking at ways to eliminate some of the exemptions that until now did not produce any result, like extending VAT to financial and insurance services or the letting of immovable properties. From that point of view, the launch of a consultation document Review of existing VAT legislation on public bodies and tax exemptions in the public interest by the EU Commission is an interesting initiative. Another one is the so-called Henry Review’s tax on financial services in Australia which suggests that : “in consultation with the financial sector, the Australian government could develop an alternative method of taxing domestic consumption of financial services … to ensure that it is treated equivalently to other forms of consumption”.

- One last area affecting the potential efficiency of VAT systems is its ability to deal with the development of what is more and more called the digital economy. Already in the mid 90’s at the OECD and at the EU level we could see the calls for adapting our VAT systems to the new development of e-commerce. Nowadays the problem in some cases is more dramatic and solutions implemented in some areas, notably in the EU, must be closely examined by all those interested in taxing all forms of electronic services, domestic or imported. In this respect, close coordination is essential to address uncertainty, risks of double taxation and unintended non-taxation that would otherwise result from inconsistencies in the application of VAT to international trade, notably when it concerns trade in services and intangibles. This is the main purpose of the OECD International VAT/GST Guidelines. Developing in parallel the ways and means of a mutual assistance and administrative cooperation capable of implementing the necessary tools for exchanging information on VAT/GST will be crucial for dealing with the challenge of the digital economy and the rapid growth of the digital transactions worldwide. In this regard, the OECD Public Discussion Draft BEPS Action 1 : Address the Tax Challenges of the Digital Economy (24 March 2014 – 14 April 2014) provides an excellent tool for examining coordinated solutions.

The OECD reports about the same figures on average for its member countries. How to improve it ? The reply clearly differs between the two groups of countries. Two main factors can explain the C-inefficiency : a “policy gap” (where VAT is not applied at a single rate and/or not to all consumption, notably due to exemptions) and a “compliance gap” (where implementation of VAT is imperfect). In advanced economies, the policy gap is the main determinant of the lack of efficiency, reflecting extensive exemptions and out-of-scope provisions as well as frequent use of multiple rates. The IMF estimates that halving the policy gap would on average raise 2,3 % of GDP (of which a substantial part would remain even after adjusting social transfers to protect the poorest from price increases subsequent to the elimination of multiple rates) while halving the compliance gap would only bring 0.4% of GDP ! In emerging markets, compliance gaps are much larger and problematic, notably in countries having implemented sub-national VAT systems leading to cascading and high complexity.

The OECD reports about the same figures on average for its member countries. How to improve it ? The reply clearly differs between the two groups of countries. Two main factors can explain the C-inefficiency : a “policy gap” (where VAT is not applied at a single rate and/or not to all consumption, notably due to exemptions) and a “compliance gap” (where implementation of VAT is imperfect). In advanced economies, the policy gap is the main determinant of the lack of efficiency, reflecting extensive exemptions and out-of-scope provisions as well as frequent use of multiple rates. The IMF estimates that halving the policy gap would on average raise 2,3 % of GDP (of which a substantial part would remain even after adjusting social transfers to protect the poorest from price increases subsequent to the elimination of multiple rates) while halving the compliance gap would only bring 0.4% of GDP ! In emerging markets, compliance gaps are much larger and problematic, notably in countries having implemented sub-national VAT systems leading to cascading and high complexity.